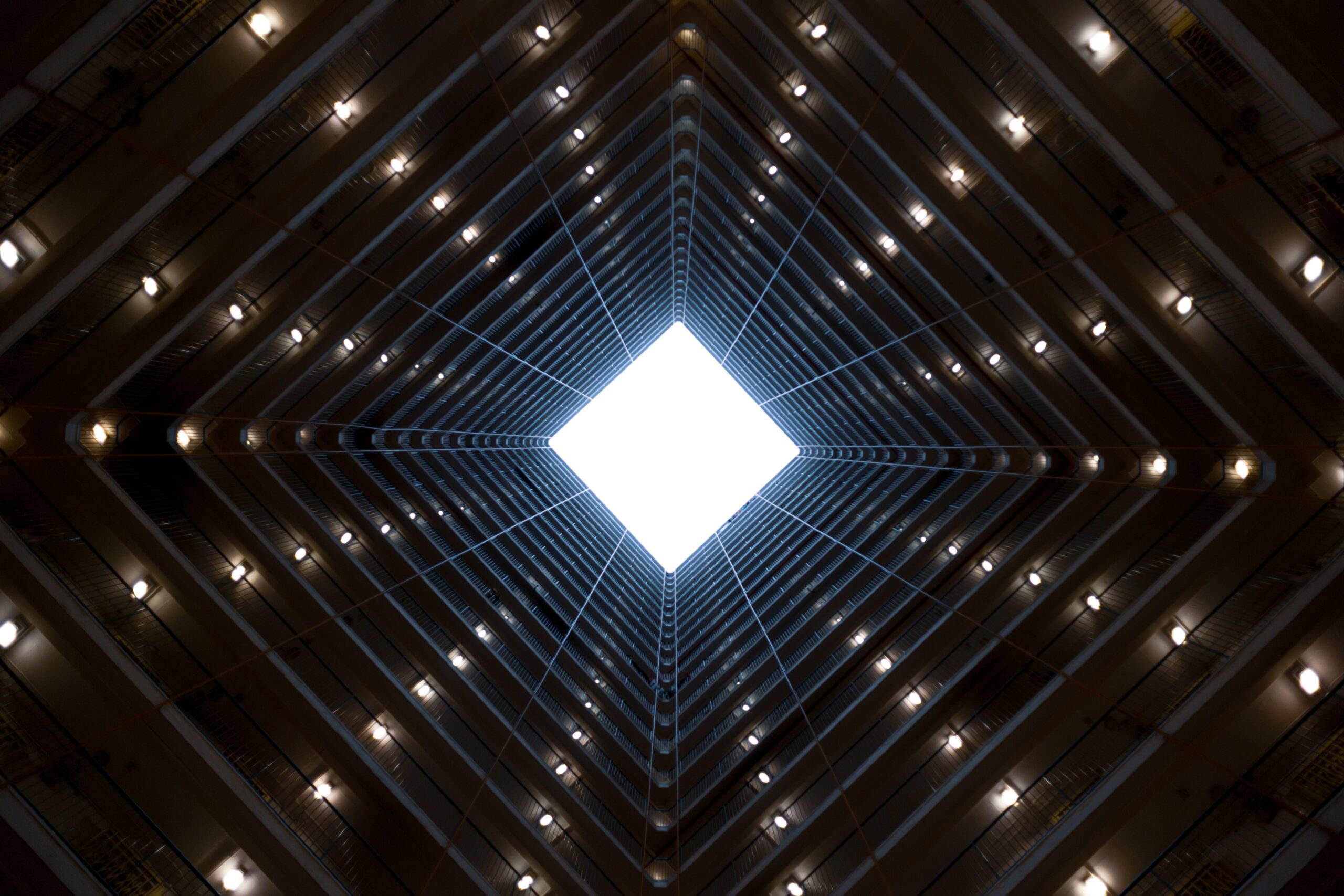

At the end of the second season of The OA, the series’ protagonist falls from a great height. Then the lights go up. We see that she’s in a film studio. Concerned crew members rush around the lead actress, calling her by her actual, real-life name — Brit. She is pulled into an ambulance. Just […]