FILM TV

Ripley, Baby Reindeer & Streaming’s Next Wave of Male Antiheroes

There was a time when television’s most compelling male leads were gangsters, teachers-turned-drug-lords, or ad men with god complexes. Tony Soprano, Walter White, and Don Draper paved the way for today’s moody TV antiheroes to brood and cheat and lie, and act out their borderline personality disorders, yet still somehow make us root for them.

Now, as we wade through the era of streaming dominance, two new contenders have entered the antihero hall of fame: Tom Ripley of Netflix’s Ripley and Donny Dunn of Netflix’s viral hit Baby Reindeer. This nouvelle vague of shows is shocking because their antiheroes are far from the Golden Age of prestige TV.

They’re not driven by power or greed. They’re shaped by obsession, self-loathing, and a fragile kind of masculinity that makes them less mythical, more intimate, and unsettling.

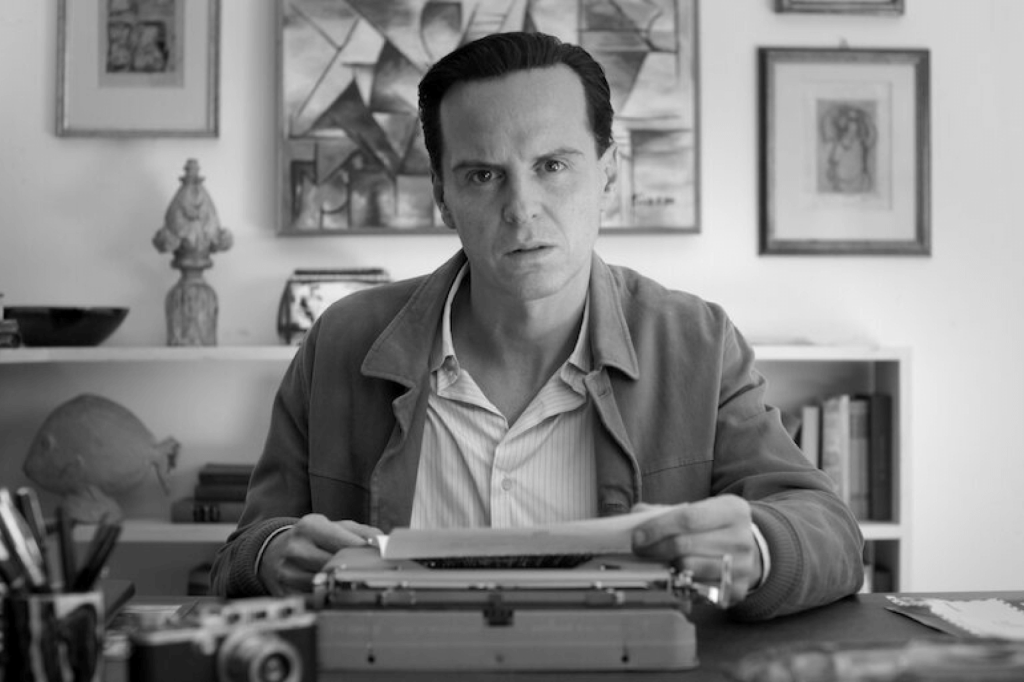

Ripley, In Black and White

If you haven’t yet been seduced by Netflix’s glossy noir retelling of Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr. Ripley, you’re in for a slow, delicious burn. Ripley is an eight-episode moody masterpiece shot entirely in black and white, directed by Steven Zaillian. It’s heavy with tension and intensity that makes you lean in and wonder what comes next.

Andrew Scott, famous for his chaotic energy (the Hot Priest in Fleabag), trades charm for dead-eyed precision as Tom Ripley. He isn’t seductive in the Jude Law-Matt Damon 1999 sense. This Ripley is colder, queerer (in sexuality and vibe), and more patient. He lies because he can. Kills because he has to.

Manipulates because it’s second nature. And we watch, not to root for him. He’s toxic, manipulative — probably a sociopath — and still, we can’t look away.

That grip he has on us is all down to how Andrew Scott plays Ripley. Each pause, each stare, carries weight. He barely speaks and rarely emotes, but still, you feel everything.

Baby Reindeer and the Unraveling of Donny Dunn

Then there’s Baby Reindeer, a show that forces you to take a break between episodes just to process your feelings. Created by and starring Richard Gadd, this is a story and a confession.

It begins with a stalker. It ends with a man fully stripped bare. Along the way, it guts you. Gadd plays a fictionalized version of himself, Donny Dunn, a struggling comedian with repressed trauma and a savior complex.

He invites a woman into his life who grows increasingly dangerous. But the real danger is Donny’s inability to let go of shame, be honest, or set boundaries. We see his worst choices and most painful memories in raw, harrowing detail.

There’s something excruciatingly honest about Donny. He’s not written to be likable. He’s needy, messy, and complicit. And that’s the genius of Baby Reindeer: it draws you in. You’re pulled into Donny’s dysfunction, forced to sit with the discomfort, and maybe even recognize bits of yourself in the mess.

The Antihero Gets Personal

These protagonists break the mold — they’re a different breed than Tony Soprano or Walter White. Those men were archetypes: alpha males grappling with power and decay. But Ripley and Donny are lonely and awkward.

Their damage isn’t buried behind mob drama or drug empires — it’s raw and painfully psychological. And, often, disturbingly quiet. Streaming has shifted the landscape. Historically, traditional networks demanded big stakes and bigger explosions.

Streaming allows for slow character studies, long silences, and morally gray protagonists who spend more time internalizing than scheming. Ripley is all atmosphere and tension. Baby Reindeer hits like a confession you weren’t supposed to hear. It’s exposure therapy disguised as TV.

And let’s not forget the cultural moment we’re in. Audiences are more trauma-literate than ever. We recognize narcissism. We talk about boundaries. Shows like these reflect that awareness.

We’re watching men wrestle with the shame, mental health issues, and the toxic masculinity that shaped them.

The Blurring of Reality

Part of what makes this new wave so disarming is how it messes with our sense of reality. Ripley may be fiction, but it feels eerily grounded. There’s no flash, no score. Just creepy pauses, like a true-crime documentary that forgets it’s scripted.

Meanwhile, Baby Reindeer walks the tightrope between art and autobiography, and the internet’s obsessed with figuring out what’s real and what’s dramatized. We want to know these men. Understand them. Maybe even fix them. That says as much about us as it does about the shows themselves.

Netflix called Baby Reindeer one of its most-watched shows of 2024, with over 56 million views. But it also sparked meaningful conversations about consent, abuse, and the ethics of storytelling.

While less viral, Ripley has garnered critical acclaim for its artistry, proving that viewers still crave slow, beautiful, psychologically rich television when it’s done right.

Why We Keep Watching

We’re living in an age of complicated men. But unlike the glorified antiheroes of the past, this new wave doesn’t want your sympathy. It wants your scrutiny. These characters are less about power and more about the fragility beneath the surface. Ripley is a sociopath who blends into high society by mimicking it. Donny is a victim and a perpetrator at the same time.

Perhaps that’s why I watch these series. Not because I admire these men or identify with them, but because I recognize them. I’ve met men who — in one way or another — resemble Ripley and Donny. Many of us have.

They’re the ones who spiral quietly, who mask control as charm, whose pain turns treacherous when it goes unspoken for too long. And unfortunately, many people have had to pick up their lives in the aftermath. And watching these characters play out their damage on screen feels familiar, like tracing the shape of something you’ve already survived.

Prestige TV gave us mob bosses and meth kings. Streaming features shows with fragile male protagonists who are falling apart.