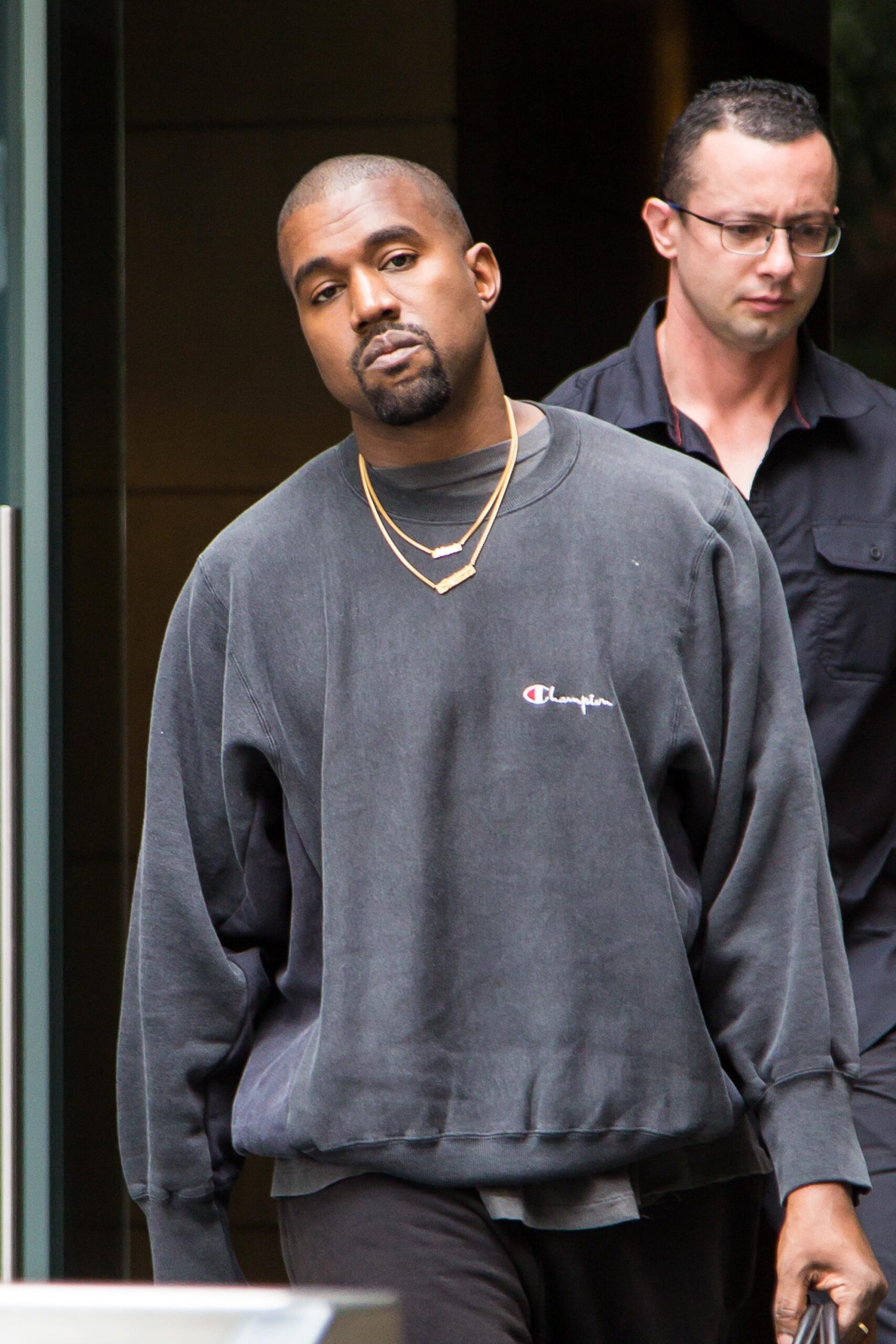

Kanye West

By Liam Goodner // Shutterstock

Ye — the artist formerly known as Kanye West — is always spouting off about something. Recently, he decried NFTs, had some very Divorced Dad moments, and hurled proverbial shots at Pete Davidson.

His latest target: Black History Month.

On his Instagram page, Ye posted that he — yes he, himself, unilaterally — is rebranding Black History Month as “Black Futures Month” with the hashtag #BFM.

This is not Ye’s first time taking shots at Black History Month. During the November 21st, 2021 episode of Drink Champs, Ye stated: “I need Black Future Month. I need Black Possibility Month.”

As they say, a broken clock is right twice a day. Parts of Ye’s BHM-to-BFM campaign make sense. “I’m tired of seeing us getting hosed-down. I’m tired of talking about slavery,” he said. And — for the most part — I agree with that element of his reasoning.

As many in the Black community have noted, there’s a problem with the way this country has traditionally taught Black history. From history books, textbooks, to the greater national consciousness, too much of what we know as Black History is centered on trauma and pain.

As Ye put it, there’s more to Black History than slavery and hoses. His frustrations with the overproliferation of traumatic, violent imagery are valid. However, when it comes to his takes on Black culture and Black history, Ye’s own backstory must be taken into account.

It wasn’t too long ago that Ye was hot on his ego-fueled, misguided run for President. During that campaign, he let loose many inflammatory statements during various press events. Most notably, that he views slavery as “a choice” and that Harriet Tubman “never actually freed the slaves.”

Ye’s blatant misunderstanding of what slavery was is most likely reflective of the culture at large. We’ve been taught a sanitized version of the atrocities committed to enslaved people and told to focus on Lincoln’s emancipation proclamation rather than how slavery is integral to the success of American capitalism. So, Ye’s ahistoricism is the least of our worries.

In fact, Ye’s brazen and insistent ignorance is proof of why we need Black History Month. While there needs to be a more holistic view of Black history, it’s necessary to fully comprehend this country’s complex racial past. It’s crucial to carving out a better future. We cannot only talk about slavery and civil rights, we also must discuss them in tandem with the nuances and triumphs and other neglected aspects of Black history.

Ye’s insistence on Black Futures Month feels like a dismissal of a history he’s chosen to co-opt for his own brand. His warped perspective on slavery comes from the self-aggrandizing narrative about being-self made. And that if everyone simply chose not to be oppressed — as he did — they wouldn’t be.

But navigating this country’s omnipresent structural inequality is more difficult for those of us who are not unhinged billionaires, who get away with doing actively damaging things. Many of us are not so easily welcomed in most spaces, nor so easily forgiven for our missteps. Racial dynamics may often play out interpersonally, but there’s more to them than individual action.

Teaching Black history is crucial to understanding this, especially when we shift the framework from “things that happened to Black people” to “systems which were upheld and perpetuated by whiteness and complicity.”

Interrogating the roles people still play in upholding power structures and inequality yields a better comprehension of where those structures come from. If we don’t, we’ll just have a repeat of the post-racial mythos that clouded the Obama presidency. We all witnessed how that ended … with Trump.

According to The Atlantic, the postracial myth points to a national failing to recognize what racism truly is and how deep it goes. “The postracial myth was first propagated by liberals who were eager to avoid grappling with persistent inequities. Back then, many liberals were stepping over the reality of inequality to fantasize that the nation had done the impossible — elected a Black president — because it had overcome racism …And now, even though Trump’s ghastly presidency and the ghastly murder of George Floyd awoke many liberals to the need to build an anti-racist nation, many conservatives have seized on the postracial myth to fight those efforts.”

In either case, the post-racial myth is the product of a deep misapprehension of history, and a refusal to engage with it — the same blatant commitment to ignorance that Ye displays.

According to a 2016 New York Times essay on the Trump victory, “There has never been a moment in America in which black people’s gains have not been perceived by some white Americans as their loss. And history is littered with examples of how economic and racial anxieties can create a wedge with which to destroy interracial political and economic alliances.”

Discerning how history repeats itself is essential to digging out the root cause. The very definition of the word “radical” is to get at the root. Ye’s pointing forward to Black Futures is not as radical as he thinks, because he’s not getting to the root of anything.

Instead, he struts about in his world of capitalist accumulation and glamour. Living it up in a version of Blackness that exists as a facade of culture without acknowledgment of the inequality that persists despite his own seat at the head table. Ye believes that he — himself — is the Black future, but I’m not satisfied with this either.

His rebranding fails to take into account the work of afro-futurist theorists already working to imagine and generate a more liberating version of Black Futures. A myriad of futures that do not depend — like Ye’s whole success depends — on the oppressive structure of capitalism and the endorsement of exploitative brands and companies.

In 2020, writer/curator/activist Kimberly Drew and New York Times staff writer Jenna Wortham edited a collection of art and essays titled, you guessed it, Black Futures. This book does the job of imagining, analyzing, and bringing together multi-disciplinary perspectives on Blackness that Ye didn’t manage to accomplish.

Black Futuresshares what it is to be Black and alive right now — offering more hope than Ye’s BFM. We can’t achieve it by glossing over that past, but by embracing it.