Tv

Netflix Kills Art with Product Placements: “Stranger Things” Brings Back New Coke

23 May, 19

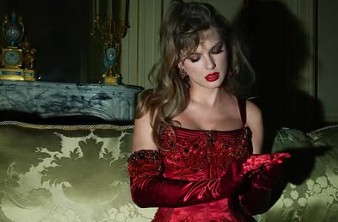

Stranger Things

Photo by kavi designs (Shutterstock)

One of the peak moments of collective American activism took place in the 1980s when Coca-Cola released New Coke, a sweeter, “smoother” product with a taste eerily similar to Pepsi.

Later described as “a taste tragedy,” what followed were boycotts, hate mail, and thousands of angry phone calls to Coke’s headquarters. But luckily for Millennials (and the $172 billion Coca-Cola company), New Coke is making a comeback, thanks to Netflix’s dedication to “programmatic product placement,” or interrupting our favorite storylines with weird, useless advertisements.

On Thursday, Coca-Cola will re-release a limited supply of its failed beverage in honor of Stranger Things. The upcoming third season is set in July of 1985, and creators Matt and Ross Duffer have taken pains to procure New Coke to appear in several episodes. The brothers claim that including Coca-Cola’s failed marketing ploy is a matter of authenticity, telling The New York Times, “It was one of the first ideas in our Season 3 brainstorm…It was the summer of ’85, and when you talk about pop culture moments, New Coke was a really big deal. It would have been more bizarre to not include it.”

It’s also a convenient product promotion worked into Netflix’s $12 billion content budget. Last year, Bandersnatch integrated brand advertisement into its choose-your-adventure style content, including one useless choice between the character eating Frosted Flakes or Sugar Puffs for breakfast. The Verge pointed out, “The choice to involve Sugar Puffs, a real cereal that rebranded as ‘Honey Monster Puffs’ in 2014, seems engineered to deflect any accusations that Bandersnatch accepted ad money from real-world products. But the question still stands: would a backend marketing deal between Netflix and Kellogg’s or General Mills have made any difference to Bandersnatch viewers?” No, of course not, because the goal of “subtly” incorporating products into content is the company’s ideal marketing strategy.

The Verge went on to specify the power behind this “programmatic product placement”: “These moments are opportunities for Netflix to market to its [149 million] users while learning from them. Using the insights it gathers, Netflix will be able to associate products with content…[and] erase marketers’ greatest obstacle by hand-holding them to their most receptive audiences.”

Integrated product placement encourages consumers to create a personal connection to brands as part of their viewing experience. Netflix has confirmed that they’ve formed partnerships with about 75 brands just for Stranger Things. While Bandersnatch brought “interactive marketing to a new level,” Stranger Things consistently appeals to viewers’ nostalgia, from characters dining on Kentucky Fried Chicken or Eggo Waffles to sipping TAB while playing UpWords after binging their Trapper Keepers home from school.

Now, “the return of New Coke is perhaps the most surprising and nostalgia-inducing element of the broader publicity effort,” according to The New York Times. Barry Smyth, the head of Netflix’s partnership marketing, said the promotion started as a joke between the Duffer brothers and Netflix executives. “We asked the question, ‘What would really blow it out of the water for this campaign?’ They jokingly said, ‘Bring back New Coke.’ They thought it was a joke. We took it as a brief.”

So what does this mean for the quality of content and what exactly does Netflix gain? Even though Netflix claims that companies like Kellogg and KFC did not pay to appear in the program, they’re clearly laying a foundation for an entirely new avenue of marketing revenue. One media executive, Jordan-Leigh Connelly, pointed out, “Strictly speaking, Netflix’s data and pattern discovery could provide insights into trend analysis that traditional simply cannot provide as it is indicative of real-world decisions like product preference, and musical taste.” But at what cost to the user, and for that matter, the quality of content? Connelly added, “This could alienate users who pay for the ad-free experience and the platform would have the added challenge of dealing with the same issue with lack of transparency that programmatic [marketing] sees today. I for one would not be happy if advertising started interfering with my favourite TV shows no matter how much I enjoy a bowl of Frosties.” In fact, the main reason Stranger Things’ throwback products are so impactful on viewers is because “the almost forgotten artifact[s] belonged to a predigital time of fewer entertainment options, with network TV still dominant, and fewer soda varieties, too”—as well as more transparent relationships between marketers and creators.

In truth, the practice of “subtly” advertising products in the guise of organic content is the bane of art in the digital age. Aside from potentially disrupting storylines with useless details (even worse than Bandersnatch’s red-herring choice between breakfast cereals), advertisers could easily gain power over characters, plotlines, or whole projects, depending on what products they’re looking to sell through the storyline. Frosted Flakes for Sugar Puffs? Coke or New Coke? These meaningless details are potentially worth millions in ad revenue and, more importantly, consumer data. Netflix is branding itself as the company that knows you best.

- Drink like it’s 1985: Coca-Cola revives New Coke for Stranger Things 3 ›

- New Coke was a disaster. ‘Stranger Things’ is bringing it back … ›

- New Coke, from 1985, makes comeback with ‘Stranger Things’ ›

- New Coke Was a Debacle. It’s Coming Back. Blame Netflix. – The … ›

- Stranger Things Have Happened: Inside New Coke’s Limited … ›

- New Coke is back after 34 years. Thank ‘Stranger Things.’ ›

- Coca-Cola is bringing back New Coke in honor of ‘Stranger Things … ›