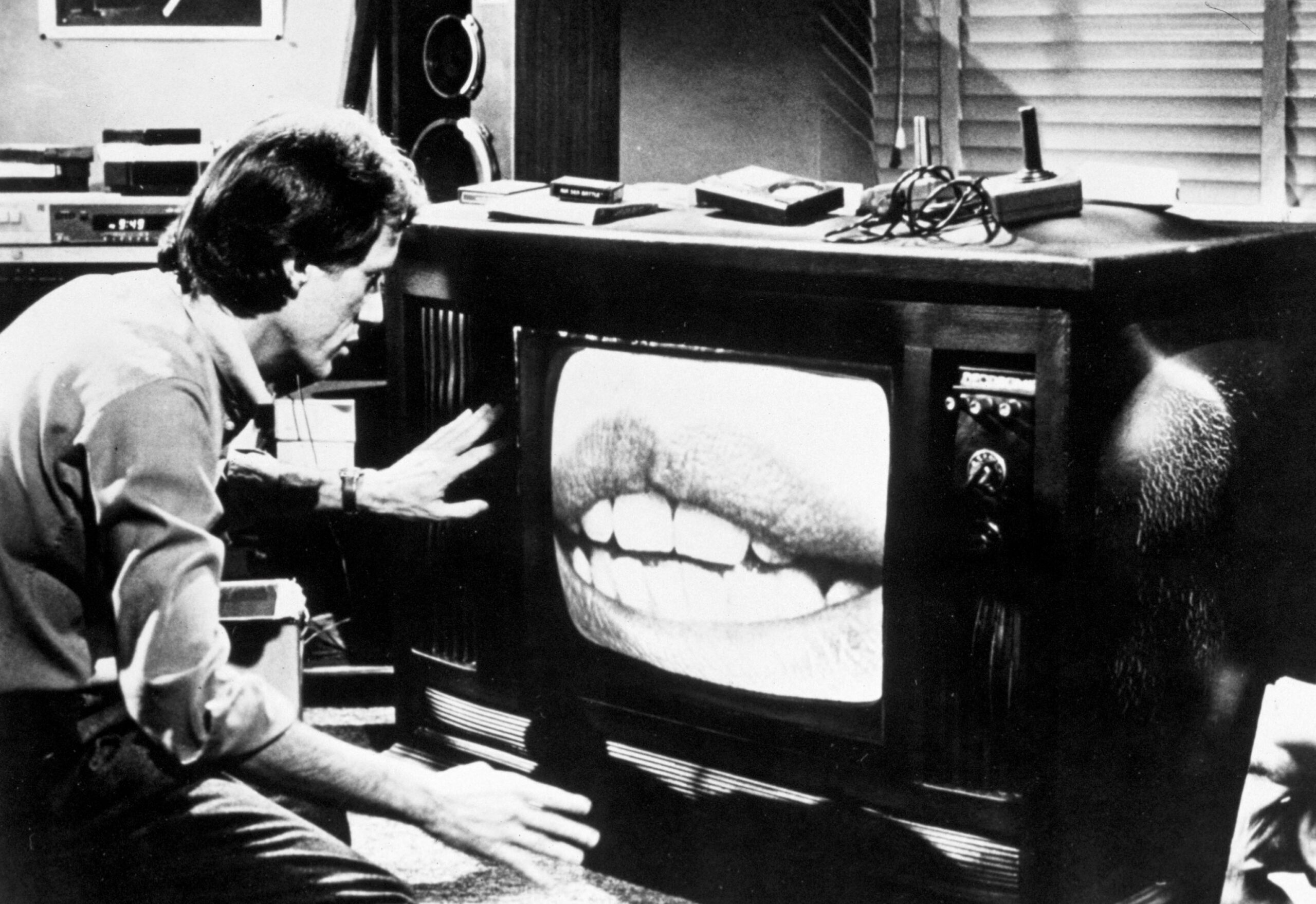

'VIDEODROME' DAVID CRONENBERG, w/ JAMES WOODS IN 1983

Snap/Shutterstock

One of the most impressive feats a film can accomplish is becoming more relevant as the years pass.

The events that swept 2020 were way more terrifying than films like Contagion or Get Out could even begin to depict. But a cult classic horror film, Videodrome, comes startlingly close to today’s real-life terror as it challenges our loyalties to mainstream media.

Videodrome is a sci-fi psychological thriller written and directed by body horror whiz David Cronenberg. Released in 1983, it stars James Woods as the president of a Canadian ultra-high-frequency TV station, where he broadcasts violent and sensational material not typically suitable for daytime viewing. One of Max’s satellite dish operators shows him a clip from Videodrome, a plotless series that shows subjects being brutalized, tormented, and in some cases, murdered.

As Max learns more about Videodrome‘s cruel origins and intentions, the film’s underlying messages become especially haunting — even more so now in 2021 than they were originally in 1983. While Cronenberg’s film was a box-office bomb, it’s since become known as an exemplary archetype of the body horror genre. A favorite among movie buffs and horror enthusiasts, it continues to be referenced today as a film ahead of its time.

(Warning: Spoilers ahead.)

Max is easy to dislike right off the bat. He’s sleazy and doesn’t consider ethics when it comes to his job and the programs he decides to air on his TV channel. He thinks Videodrome is the future of entertainment to come — that is, until his new sadomasochist girlfriend Nicki (Debbie Harry) decides to audition for the show, potentially subjecting herself to unfathomable degrees of violence. Suddenly, Max is no longer the villain; Videodrome is.

Videodrome (1983) – Trailer HD 1080pwww.youtube.com

Initially, Max believes Videodrome to be fake; no way could such terror actually be shown on television. But when Nicki doesn’t return from her audition, Max feels compelled to find out the truth behind the show.

Max discovers that the events in Videodrome are, in fact, real. Not only that, but Videodrome isn’t just a TV show; it’s a socio-political movement driven by a desire to replace every aspect of normal life with television. Watching the show subjects its viewer to hallucinations and a malignant brain tumor. Suddenly, Max is punished by the very thing he initially swore would be the future of TV.

With Videodrome, Cronenberg offers a multitude of potential takeaways. Does consuming violence and explicit sexual content make us evil? Is overconsumption of technology in any form dangerous? Videodrome asks an array of questions that might never be answered, but they’re even more relevant today.

At the risk of sounding like a boomer, technology is more prevalent than ever, and the ways in which it trickles into everyday life are difficult to keep up with. VCRs had fairly recently become a common household item at the time of Videodrome; today, some of the most famous people in the world ascended to their status because of TikTok, an app that former president Donald Trump infamously threatened to ban in the United States.

Media has long impacted the course of history. But in the context of the past year, it’s played a much more nefarious role in many instances. Forums like QAnon and Parler serve as a safe haven for right-wing extremists who have been filtered out by Twitter and Facebook. How far should “freedom of speech” reach? How do we determine what is harmful for the public eye, and who makes those decisions?

While Cronenberg never taps into left- vs. right-wing policies with Videodrome, the film shines a light on how easily humans can find themselves brainwashed by mainstream media. In the film’s latter half, Max can no longer determine what he’s hallucinating and what is actually happening in front of him, even in circumstances that seem too insane to be true. Ring a bell?

When Max finally meets Barry Convex, the producer of Videodrome, he learns that he’s been sought out and recruited for their mission: cleansing North America by killing, via brain tumor, everyone mentally twisted enough to watch Videodrome. Tormented by the choice of whether to continue broadcasting Videodrome or not, Max ends up — unsurprisingly — killing himself in the film’s final scene.

As the 2020 documentary The Social Dilemma pointed out, we’re living in a time where media affects nearly every aspect of our lives, to the point where the lines between media and reality are imperceptibly blurred. Who controls the media at large? And what happens when we become so desensitized to what we’re being fed digitally?

Videodrome is a heartbreaking film because it offers no clear-cut solution to avoiding the dangers of media. Like The Social Dilemma, it lays out these issues in a harrowing light; but with Cronenberg’s affinity for practical effects and striking filmography, Videodrome is arguably the most terrifying film in this category. How will you subvert the potential brainwashing that comes with gluing your eyes to the screen?