"Lovecraft Country" Reminds Us That Magic Is as Real as We Believe It Is

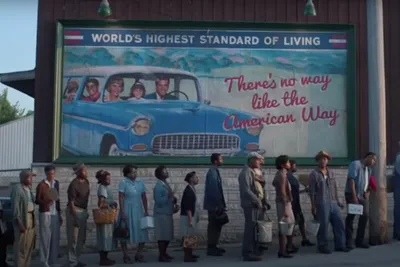

One of the ideas explored by HBO's Lovecraft Country was the meta-boundary between fiction and reality—not only for the characters of the show, but also for us, the viewers.

The show (which is based on a book called Lovecraft Country by Matt Ruff) finds Tic, his love Leti, and his father Montrose contending with the storyline of an autobiographical book (also called Lovecraft Country) written by Tic and Leti's future son.

One of the earliest episodes mentions the Necronomicon, an infamous book of magic featured in H.P. Lovecraft's fiction stories. This is an acknowledgement of the 100-year-old Lovecraftian world of antediluvian terrors.

But the way Lovecraft Country introduces the esoteric arts is very much aligned with real history. Magickal lodges with secret initiations exist. Voodoo priestesses exist. Korean shamans, called mudang 무당, exist and even influence top-level politicians. Lovecraft Country and HP Lovecraft''s legacy constantly interrogates the boundaries between fiction and reality, asking readers to question their own realities as well as their capabilities to create their own worlds or influence them through stories.And people doing rituals calling upon the terrifying entities from Lovecraft's stories exist. For a long time, fans of HP Lovecraft have attempted to blur the boundary between fiction and reality, sometimes even writing fiction into reality by performing rituals that summon the terrifying entities from Lovecraft's stories. So, not only do people doing these rituals exist—they have and continue to experiment with ways to successfully work with the plasticity of identity, re-evaluating what is defined as "real vs. fake" in the process.

"Fictional works—especially horror or fantasy—strike me as an opportunity for the mind to consider things far beyond the dominant reality," says Victor LaValle, author of The Ballad of Black Tom, a multi-award-winning fiction story that adds much-needed subversion to Lovecraftian mythos by centering the narrative around a Black man who has the power to summon alien entities called the Old Ones. "I view writing as a form of labor that, at times, reaches something beyond labor, whether that would be called art or...reality-shifting."

The Necronomicon and the Power of Fanfic

"Lovecraft Country" takes place in a parallel past, where aspects of American sci-fi/horror writer H.P. Lovecraft's stories are "real." This reality includes Shoggoths, which are monsters that were genetically engineered by the Old Ones.Shoggoths are part of the Cthulhu Mythos, which is about how "alien gods [the Old Ones] once ruled the cosmos, until they fell quiescent for unknown reasons," says Daniel Harms, author of The Necronomicon Files and Cthulhu Mythos Encyclopedia. "Cthulhu, the squid-headed dragon-winged monster, is the most famous. Someday they will rise again to re-take the world. Certain cults circulate strange books and perform rites to speed the return of the Old Ones, who nonetheless are largely indifferent to human concerns, emotions, and goals."

Lovecraft built complex worlds, aspects of which he would mention again and again in different stories. Alongside the Cthulhu Mythos, the most popular Lovecraftian stories involve the Necronomicon (also known as The Book of the Dead), which was first mentioned in Lovecraft's story "The Hound."

The book has a fantastical backstory: the "Mad Arab" Abdul Alhazred wrote Kitab al-Azif (later called the Necronomicon), a book about the worship of Chthulu and Yog-Sothoth (another Lovecraftian entity). All those who work with the Necronomicon meet a horrific demise, and according to H.P. Lovecraft in his short story "History of the Necronomicon":

Of [Alhazred's] final death or disappearance (738 A.D.) many terrible and conflicting things are told. He is said by Ibn Khallikan (13th-century biographer) to have been seized by an invisible monster in broad daylight and devoured horribly before a large number of fright-frozen witnesses.

Of course, this is pure fiction, says Daniel Harms. "The title Al Azif is a straight lift from a footnote in William Beckford's Vathek, and [Lovecraft] was talking about his desire to find actual works of magic years after he invented the Necronomicon."

This hasn't kept other writers and fans from speculating about the veracity and existence of the Necronomicon. In the 1970s, fanboys insisted the Necronomicon was actually the Picatrix, a famous 11th-century book on Arabic astrology and magick (it wasn't). Even recently, there has been speculation that the Necronomicon could be Shams al-Ma'arif (spoiler alert: nope, and as Daniel Harms says: "deciding a book of magic inspired a fantasy author just because it's also in Arabic is its own manifestation of Orientalism").

Today, when people say they've read the Necronomicon, what they really mean is that they've read the version nicknamed the Simonomicon, which is "by far the best selling occult book of the century [and]...can be purchased at almost every bookstore in America," according to an interview occultist Jason Miller did with the mysterious editor, known simply as "Simon."

"The Necronomicon is a fascinating example of memetic structures or items infiltrating and warping the real," says Scott R. Jones, author of When The Stars Are Right: Towards An Authentic R'lyehian Spirituality, a book on how to work with Lovecraftian deities. "Like everything [Lovecraft] wrote about, the Necronomicon never existed. [But] it wants to exist. Like, real bad. And it ropes in naive readers of Lovecraft with the idea that it could exist [because] Lovecraft...cleverly inserted the Necronomicon on his character's bookshelves, slipping it in between real occult books like Blavatsky's Secret Doctrine, Margaret Murray's The Witch Cult in Central Europe, and Sir James Frazier's The Golden Bough. Books like that gave the Necronomicon an air of verisimilitude that's never really left the thing."

The Simonomicon is still treated as the real-life Necronomicon by many young occultists. After Daniel Harms' book The Necronomicon Files was published, "'Simon' came out of retirement to convince HarperCollins to write a Necronomicon sequel to try to debunk us, and HarperCollins ended up revealing that he was [occult historian] Peter Levenda through their own copyright filing [although Levenda denied he was Simon in 2013 for an interview with The Verge]," Harms said.

Who Gets to Define the "Realness" of Magic?

"Fundamentally, what I think 'magic' is about is 'consciousness' and, more specifically, the mind-matter relationship, which is much more complicated and mysterious than we normally imagine," says Dr. Jeffrey Kripal, the J. Newton Rayzor Chair in Philosophy and Religious Thought at Rice University and author of Mutants and Mystics and The Super Natural. "I often write about 'the trick of the truth,' by which I mean that sometimes it takes fantasy or fiction to have a paranormal effect in the material world. Belief DOES matter, but that does not mean that 'it is true.' What it means is that 'it works.'"

One of the most compelling magical texts that helped shape a generation of occultists into this 'trick of the truth' mindset is Phil Hine's Pseudonomicon, which, unlike the Simonomicon, never claimed to be the original text. Instead, after stating that "there are no Necronomicons," Hine then extols the "core feature of the Cthulhu Mythos…[which] is Transfiguration--evolution into a new mode of being...this transfiguration brings not only a new perspective, but also the ability to live in other worlds, and a kind of self-sufficiency that does not depend on other people's views and judgements."

Working with Lovecraftian entities as if they are "real" is a reclamation of the wildness inherent in all nature, which includes aliens and starseeds. "Most magical orders tend to the view that their work is contributing...to the evolutionary development of human culture. Those who adhere to this view with respect to the Cthulhu Mythos posit that contact with the Old Ones is a process of uniting the chthonic roots of primeval consciousness to the stellar magicks of the future," Phil Hine writes in the Pseudonomicon.

The Pseudonomicon then lays out a flexible outline on how to do this transfiguration, a process with three stages: Fear the Beast, Feel the Beast, Feed the Beast.

There is a great deal of power in this aspect of the Great Old Ones-the shadowy adumbration's of power which have been long suppressed and denied, that which is beyond the 'ordered' universe which we inhabit most of the time...you have to abandon all safety and enter their world. If you return, you will return transformed.

Additionally, in the book, Hine also makes a distinction between "Theories-of-Action" ("presumed to be 'true' independently of human experience") and "Theory-in-Use" ("can only be learned by the individual by a process of practice in 'live' experience"), which can also be seen as objective versus subjective descriptions of an object or experience.

"Lovecraft was a materialist. It was his belief that his stories were fiction and that was that. People are used to clearly define areas of fiction and non-fiction," says occultist Dana Fox, who has worked with Lovecraftian magick intimately. "But in my magical life (and life in general), I have been surprised to learn that the lines between real and unreal are not so clearly defined. People have used stories to tell about real phenomena for thousands of years and, even if it was not the author's intention, Lovecraft's fiction contains a lot of truth."

Often, magick and the occult focus purely on potential external gains. But the goals of turning fiction into reality are ultimately concerned with the creation of a new personal mythos, of an identity shift that literally rearranges reality—no longer are we passive passengers of the currents of Fate, but instead we have transformed instead into the weavers of the fabric of The real.

"What I advocate in When the Stars are Right is building/writing your own Necronomicon," says Scott R. Jones. "As a book that does not exist, your obligation as a seeker is to pull it into existence. Really, it's all humans do with anything."

In essence, we are all creating our own Bibles, and we are all Gods and angels and demons alike, as much aliens of a relentlessly indifferent cosmos as the dreamer who travels to the astral planes of Lovecraft's The Lands of Dream to read through the perfect, original, Platonic form of the Necronomicon.

"This will sound blasphemous or provocative, but all religions are fictional, and they all work," says Dr. Jeffrey Kripal. "[Religions] are all cultural fictions...and they all work...the real reason religious people assume that their worlds are real and others are fictional is that they were born into these worlds, which have been constructed over centuries or millennia and so seem entirely solid or stable. They are not."

If it's a moot point whether the Necronomicon is real or not real, then the question shifts to whether or not practitioners feel compelled to call upon the Old Ones. And if they are, then what sort of personal grimoire, a book of spells, will arise from such an endeavor? In this sense, so many works of fiction, of multi-dimensional narrative, are grimoires. Amazon and Barnes and Noble are dripping with audacious magick.

"Whether or not that reconsideration changes the outside world seems less important to me than the changes such thinking can cause to our inner worlds. It can expand the scope of our imagination and our intelligence and what we can believe is achievable even in this reality," says Victor LaValle, who begins The Ballad of Black Tom with this invocation: "For H.P. Lovecraft, with all my conflicted feelings."

As the author has spelled out the symbols of their imagination, we the viewer and reader have naturally, organically partaken in the High Mass of belief. Lovecraft Country Season 1 is over, but the workings of real magick are still available in the made-up meta-ness of what we call make-believe.