How the Online Left Alienates Working Americans

If we're going to build an effective Left movement in America, it has to be accessible to people outside an educated elite.

American politics are a mess.

Even if you accept the artificial team sports dynamic — the fact that the entire spectrum of political beliefs gets artificially narrowed into two warring political factions who are disturbingly similar in terms of military and economic policy — there are some striking questions about how the division between those teams should really be understood.

For example, shouldn't working class people — who stand to benefit substantially from Left-wing policies, like an increased minimum wage, universal healthcare, collective bargaining protections, and paid family leave — be at the core of Left-wing political discourse? Shouldn't they feel welcome in the movement that is supposedly fighting for them?

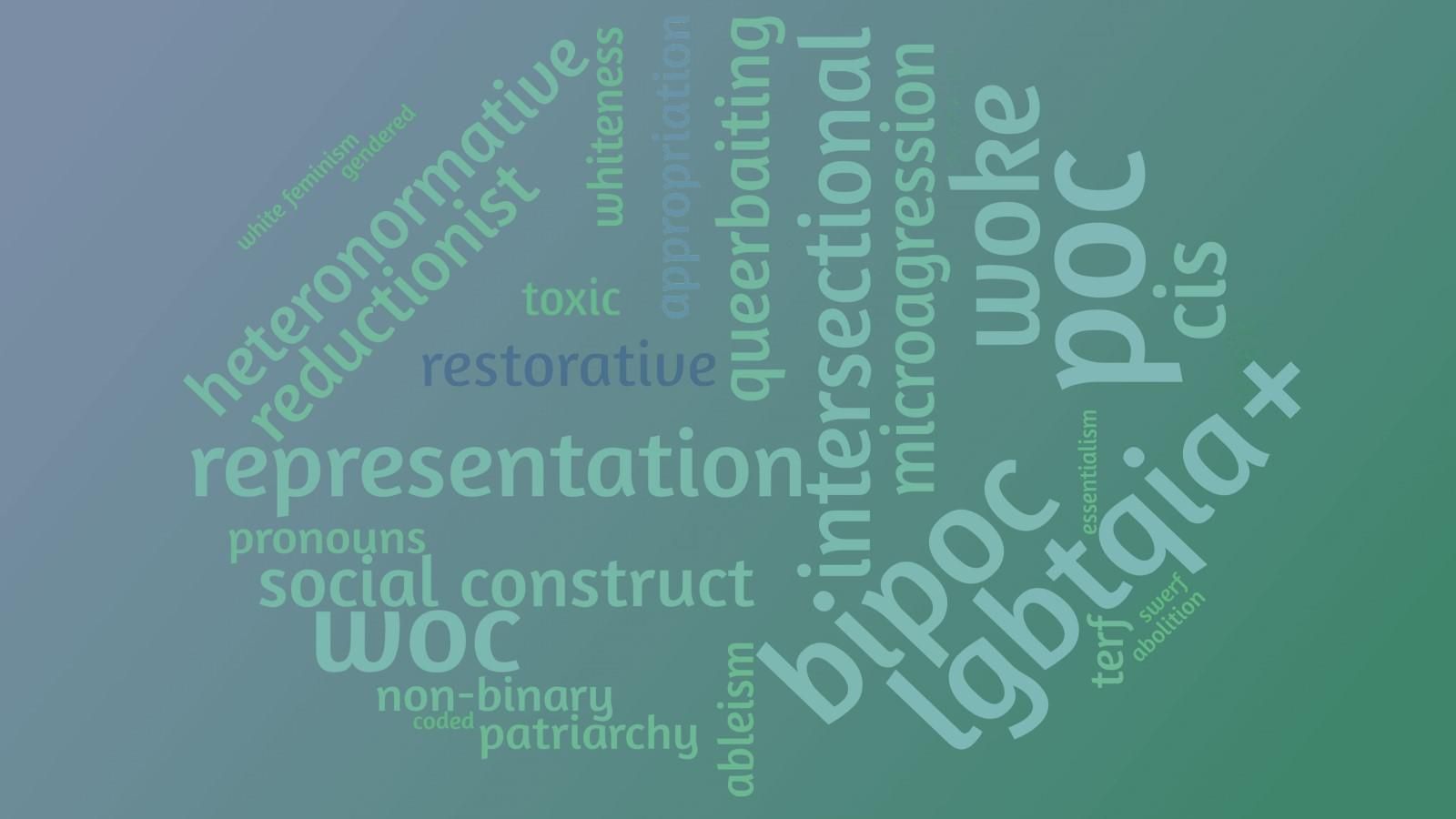

Instead — in online spaces like Twitter — the conversation tends to be dominated by a combination of earnest activists fighting for equality for marginalized groups and smug elitists who use their education to shame people who are less informed. What results is a conversation that too often focuses on reshaping and policing language to a degree that was previously unknown outside of graduate-level sociology courses.

A Barrier to Entry

"It's not 'homeless,' it's 'unhoused.' And you can't say 'slave-owner,' because the correct term is 'enslaver.'"

Rarefied, quickly evolving language — no matter how well-intentioned — alienates vast swaths of people who could theoretically be on board with the Left.

People working overtime in so-called "unskilled" jobs — driving for Uber, making fast food, or working in an Amazon warehouse to support their families — likely have plenty of motivation to improve their conditions. But they should not be required to keep track of the growing list of politically correct language just to fight for their own interests.

Often these terms are not even that helpful. Take "Latinx," for example. The desire to have a gender-neutral version of "Latina/Latino" is no doubt rooted in a thoughtful impulse, but it's been criticized for reaffirming a sense of monolithic identity that subsumes so many cultures — and, to the extent that there is a "Latinx" community, the fact that the word doesn't really work in Spanish doesn't endear it to many of the people it refers to.

But even when this new vocabulary is well thought-out and vitally important — like, for instance, "non-binary" as a term for people who aren't represented by either of the traditional genders — the fact that it is an unfamiliar concept is reason enough for many Americans (particularly older Americans) to dismiss it.

"If people didn't need it when I was growing up, why are kids these days acting like it's so important? It's just a fad."

What context do they have to know that the fight against gender constraints is more legitimate than the kids on Twitter who have labeled the parent-child relationship as oppression? If they have never felt constrained — and have only known people for whom the old binary seems to function — they will likely treat it as trivial.

On the Right the response is generally to encourage that impulse and draw them in with simplistic perspectives that bolster their biases. What is the Left's solution? To label them bigots for resisting change that they have no framework for taking seriously.

The newness of it — from this limited perspective — is a barrier to entry for all the politics that go along with it. This is a serious problem.

If they could be introduced to the reality that non-binary people have always been around and have been acknowledged by numerous cultures (though they are still subject to oppression), many of these people would probably recognize the need. But most of them won't be receiving that education anytime soon. And if they express their skepticism to the online Left, they're more likely to be shamed and shouted down than provided with any insight.

A Broad Coalition

It would be easy to say that if a person isn't curious or compassionate enough to bother educating themselves then we shouldn't want them on our team. But that is unfortunately not an option.

Because the same politics that fight for the dignity of trans and non-binary people must necessarily fight for the dignity of people who were never given access to a quality education — many of whom are now struggling to get by in work that doesn't pay what they deserve and keeps them too anxious and exhausted to invest so much academic concern in the language they use.

But rather than bring them on-board by focusing on the fact that the vast majority of people are badly exploited by our system — and could benefit from working together — there is an impulse to shame them and blame whatever privileges they nominally possess for their ignorance.

It's not that they have spent years overwhelmed by their own problems in a system that's designed to keep most people struggling. It's just that they are male, or cis, or straight, or white, or able-bodied, or neurotypical, or all of the above — even if they've never managed to reap much of a benefit from their privileged classes.

What should be a broad coalition of marginalized people who can work together to push against the inertia of the status quo instead becomes a niche community of those most eager to engage in the competitive hobby of woke political speech. And on the other side of the equation there are more than a million Floridians who voted for one of the Left's signature policy proposals — the $15 minimum wage — while also voting for Donald Trump.

Leaving aside the fact that elected Democrats have shown little interest in making good on that proposal at the federal level, this divide between social and economic politics is pervasive. So many Americans like and stand to benefit from Leftist proposals like an increased minimum wage, universal healthcare, paid leave, and union protections. But if they try to engage with the conversations that tend to go along with these issues, they will find an entire glossary of unfamiliar terms that seem designed to make them feel unwelcome.

Leftist Shibboleths

Unfortunately, it's far easier to identify this problem than it is to point to a solution. Because this is a pivotal moment in our nation's development.

As the largest and most educated generation in our history comes into its own, our culture is undergoing a dramatic shift. And it makes sense for language to evolve to accommodate those changes.

But if it continues to evolve in a way that excludes and shames people who are struggling to get by — and don't have time to devote themselves to Twitter — we will deepen the divide between the educated, elite liberal class and the exploited workers whom the Left claim to fight for. We will end up splitting the language — and our potential coalition — in two.

It's not that terms like "microaggression," "toxic masculinity," and "cultural appropriation," are make-believe — they are important issues worth recognizing and understanding — it's that they are shibboleths. They are accessible and commonplace to the in-group, but they sound like nonsense to the uninitiated — "So... not liking other cultures is racist, but liking them too much is also racist?"

They are cultural signifiers that indicate that you have a certain level of education and a certain level of empathy. But without the former, no amount of empathy is going to make these concepts comfortable.

This is not to say that people who haven't been to college can't use these terms. There are other ways people can educate themselves, but they all generally require a certain amount of time and effort, neither of which people who are struggling to make ends meet and provide for their families tend to have.

And considering the fact that nearly 24% of American adults without a high school diploma — and more than 11% of those with a diploma but no college education — were living below the criminally outdated poverty line in 2019, the online Left is not doing anyone any favors by making its discourse so exclusionary. And those figures came before the coronavirus pandemic made things so much worse.

Voting Against Their Interests

The Left has often wondered why so many poor and working white Americans seem to vote "against their interests" — that is, they vote for Right-wing politicians whose policies are focused on cutting taxes and regulations for those at the top and cutting services for everyone else. While bigotry and cold-war brainwashing are no doubt involved, this alienation from the Left's discourse is another big part of the equation.

The people most in need of Leftist policy are often the people least welcome to join Leftist discourse. The blend of academia and corporate HR-speak comes across as so affected and elitist that anyone who tries to wade in without a primer is bound to reject it.

Why should they feel that their interests could be represented by a community that doesn't even seem to speak the same language? A community that spends so much time in the weeds, discussing topics that must seem like imaginary problems?

Conversations that are reasonable to have in lecture halls and peer-reviewed journals are being treated as essential culture. How are people who don't feel at home in those contexts — who have never had access or interest in them — meant to take that as anything but antagonistic?

Why would someone without that background not prefer to side with the Right-wing demagogues shouting that it's all nonsense? They become vulnerable to the culture war wedge issues that are driving so much of the division in our country, despite the necessity and popularity of the Left's economic proposals.

Unfortunately, short of abandoning our principles, there does not appear to be a simple solution to this disconnect.

The Demographics of Leftist Twitter

In part, it's a simple matter of demographics. Twitter users — for example — are younger, wealthier, more concentrated in cities, and more educated than the general populace.

Twitter heightens the generational shift that the millennials have brought on. And while that generation may be saddled with too much debt to buy a home or start a family, a side effect is that many of them tend to have more freedom and luxury to invest in questions of aesthetics — of what language we should use in endless, fruitless conversations about fixing the world.

And while their niche conversations on social issues do not correspond directly to broader political debates — on cable news, debate stages, and in bars — Twitter's prominence in DC and the media does give them an outsized influence.

For example, take the debate around the word "racism."

Should we nod along when people use "racist" to refer simply to racial prejudice — even when it's from marginalized people and directed against members of a dominant racial group? For instance, when members of the Black Hebrew Israelites say that white people deserve to be exterminated, is that racist?

Or does it count as racist only when it's directed against another marginalized group, as when one pastor in that sect dismissed the evils of the holocaust? Or do neither count as racist, because racism fundamentally involves systemic oppression that the Black Hebrew Israelites have never had the power to participate in?

This is a real conversation in academia and on Leftist Twitter. And it may have some legitimate value in countering false equivalencies between racial prejudice that is merely distasteful and racial prejudice that is a part of real harm and oppression.

But when attempts have been made to introduce this distinction into everyday life, they have been met with severe backlash — and not just from white supremacists.

In common usage, there is no confusion about whether looking forward to the extermination of another race constitutes racism… And efforts to complicate the matter and "correct" that usage come off as disingenuous — as bad-faith attempts to blame white people for everything and bar them from conversations around race and racial hatred.

Which could honestly be fine (white people generally have the least to contribute to these conversations and are often eager to dominate them anyway) if the movement didn't need them. But if we're going to make substantive political progress against systemic racism, then we need a broad, popular movement to back it. That means some significant portion of white Americans need to engage with that conversation.

A Balance of Essential Values

We can't afford to alienate broad swaths of the population who should be on our side. And yet, as culture progresses, it is often necessary for language to adapt to those changes. So how do we find a balance between these essential values?

Does it make sense to muzzle activists who are fighting for recognition? Or should we shame and alienate working people who are broadly tolerant because they lack the time, the energy, or the inclination to learn about gender-neutral pronouns on their own, or to keep track of an abbreviation — LGBTQIA+ — that has doubled in size since the last time they knew what all the letters meant?

If the online Left is happy just to be having conversations we feel good about — sanitized, exclusive discussions that reinforce our values as educated, thoughtful people — there is no issue at all. We can take an informed position on why it's worth capitalizing Black and not white and content ourselves to roll our eyes at people who assume that means we're "anti-white."

But if we actually want to make people's lives better, we have to adjust our tactics to make our movement more accessible and inviting. We can't just tell working people that they have cis, or white, or neurotypical privilege without acknowledging that the whole conversation comes from a place of educational, geographic, and economic privilege.

We can continue to evolve and push for language that reflects our values, but we can't treat absolute and instant compliance with these changes as essential to participation in Left-wing politics. There is a learning curve.

We need to be gentler — more inclusive and welcoming of people who are out of the loop, in order to bring them in. And we need to be willing to call people out when they are needlessly complicating issues, or using their education as a means of scoring "woke points" against those who have less.

Otherwise we will just keep preaching to the choir while the church burns down around us.