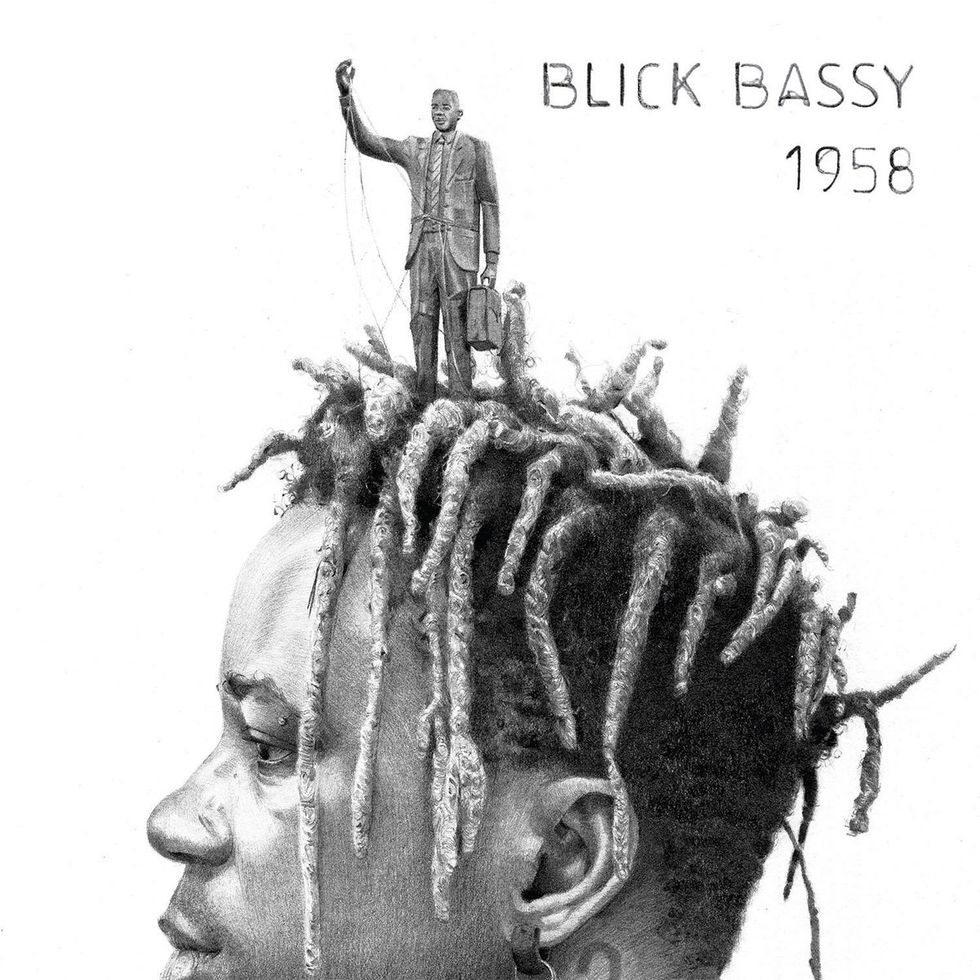

Blick Bassy's new album, named for the year a key figure in Cameroon's struggle to cast off the colonial yoke was murdered, reminds us that freedom, political stability, and material security remain elusive for many African countries.

While many of these countries are technically free from Western control, they continue to suffer from the effects of colonialism. All this and more is expressed in 1958, produced by Feist and Manu Chao collaborator, Renaud LeTang. From a mid-town skyscraper two days before appearing onstage in Central Park as a part of the "Summer Stages" concert series, Bassy spoke to Popdust about the album, his formative years spent living in the rainforest with his relatives, and the struggle to protect the integrity of his own artistic expression from outside pressures.

First of all, the new album is amazing. The production is unreal. Could you tell me something about how it was produced?

Before recording the album, I had kind of a general idea of where I wanted to go with it. The idea came during my last tour supporting my previous album: we did more than 200 gigs world wide, and when you play so much you have to make your songs sound a little different every time. During that two-year process, I also wrote about 10 new songs. Then, my band and I spent about 12 days together to arrange them.

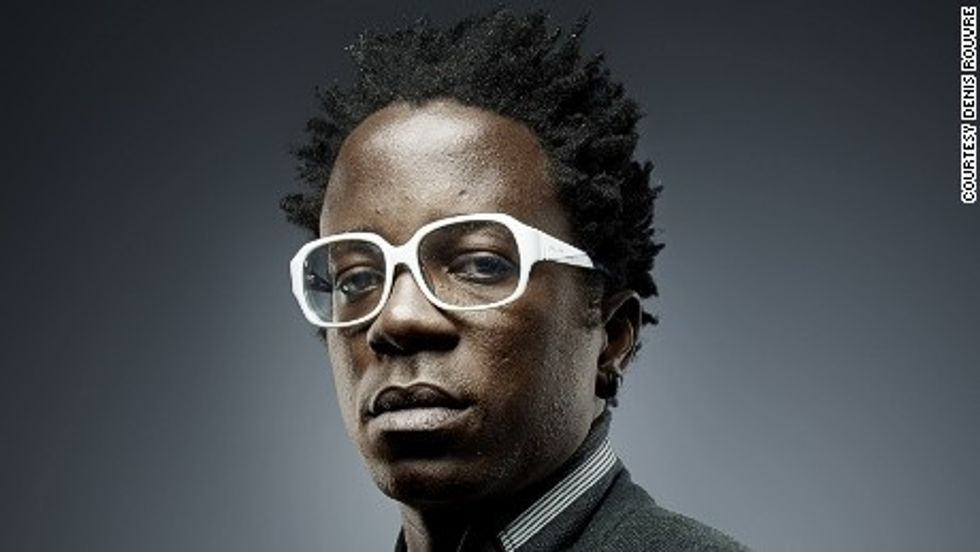

Blick Bassy

Blick Bassy

So the new album grew organically out of the last one?

Yes. But also, you know, I'm from Cameroon, I meet a lot of people and listen to a lot of different music. It's made me what I am today. I'm an African living in France and also everywhere in the world, because I'm traveling all the time. So the album represents what I am today.

What are some influences you've absorbed living away from Cameroon?

First, traditional music from Kenya, Nigeria and other African countries - actually, I have a label in Cameroon and I'm producing a lot of new music from those regions and Cameroon.

What's it called?

BB productions. But as far as music outside Cameroon, I've been listening to James Blake, David Bowie, Prince. Apart from their music, they live outside of the norms that society says we have to follow.

Your upbringing in Cameroon seems a little outside the traditional, too. For instance, you were sent to live in the rainforest with your grandfather. Is that something a lot of people in Cameroon do, send their kids to the jungle?

It was very unusual, yes, especially because my father had a lot of money. He decided that we had to live as if the world was starting again, without anything. We had to go to villages and work on farms. And, yes, I lived with my grandfather and uncle for about five years. They wanted me to understand how the world works, and how the environment works. At the time I didn't want to do it, but it completely changed my life.

You were just a spoiled kid at first?

[laughs] Yeah. But later all this came back to me when I was living in Paris. I was feeling a bit lost, and I asked myself, "What can I show to the world, me, singing in a language [Bassa] no one knows. How can I survive?" And what I was taught in the jungle, self-reliance, helped me a lot.

So it was kind of a self-esteem exercise, living with your relatives?

Exactly.

Describe your journey from Cameroon to Paris. Because you were already established in Cameroon, if I'm not mistaken.

Correct, yes. After 10 years in Cameroon with my first band, I wanted to go further. I needed to meet other humans in others spaces in the world, and share my music. Because all the music of the world was coming to Cameroon, and I wanted our music to come to them! So I decided to leave. And since I come from the French-speaking part of Cameroon, I decided to move to France.

That makes sense. The linguistic aspect of the album I find very interesting, the fact that it's all in your native language, Bassa. Furthermore, there's a lot of conflict around language in Cameroon, especially with the English-speaking peoples of Cameroon. What's your view on that issue, or is that a touchy subject?

No, no. For me, it's clear that we were educated to see [English-speakers] as only half-Cameroonian. Because I have friends that come from that region. And when we were in school, if you dated a girl in the school who came from there, it was like, "Whoa, what are you doing?? Are you crazy? They are really bizarre!" At the time, we didn't realize this would become an issue later on. When they started asking for equal treatment, the government started sending police there and killing people.

The last track of the album has an English title, and a mix of Bassa and English lyrics. So you're obviously not taking the position that English is a second-class language.

No.

Back to Paris: what was it like getting established there?

It really helped me to find myself, moving to Paris. In Cameroon it was too easy for me: my band was famous, everything was easy. Moving to Paris brought me back to my roots as a black man living in France. It helped me to understand that I HAD to sing in Bassa. What I had in my bag of tricks was my roots and traditions. But also, trying to sing in English or French was nonsense, because if you sing the same melody in another language, it will change. So those melodies in Bassa were bringing something new to the ears of [Europeans]. Also, how can I survive as a musician here? How can I connect with people who don't understand what I'm saying? I realized that the universal language was the emotion, the vibration. Not language itself.

But on the other hand the new album is thematically very specific: it's about Cameroonian independence.

Yes.

One of that movement's central figures, Ruben Um Nyobe, how does he come into play on the album?

The whole album is about him. 1958 was the year he was killed by the French army.

Ah!

When I moved abroad, I understand we Cameroonians were living in a country called "Cameroon" but it wasn't our country. It was a country that was built by other people.

They imposed it on you.

Exactly. And now we're trying to survive this. And people still think about "my country." But we don't have a country! Also, we're very restricted as far as where we can go outside Cameroon.

You can't go to certain countries in Africa from Cameroon, then?

Some, yes, others, no.

So there's not that idea of geographical and cultural unification that partly exists in Europe?

No, but I think in the next five years we'll be able to travel anywhere we want.

That's an interesting issue, the idea of "One Africa." But the continent is incredibly complex, obviously. In the media, for instance, I'm sure you've been compared to, or conflated with, other African artists. Say, Fela Kuti. But throwing you in with Fela would be like categorizing Paul McCartney with Serge Gainsborough.

[laughs] Yes. But actually, they used to compare me to a singer from around here! He passed away very young. He had a wide singing range. I don't remember his name, though.

Going back to the Bassa language, how widespread is it in Cameroon?

Well, we have 24 million people in Cameroon, and about 3 or 4 million speak Bassa. It's one of 200-something languages.

So there's a lot of linguistic diversity. Is Cameroonian music similarly diverse?

Absolutely. Every language, every tribe, has their own music, their own food, dance, the way people speak French or English. This makes the country culturally very rich.

Because, really, it's many different countries.

Exactly. They used to say about Cameroon, that it's the whole continent of Africa in one small country.

A kind of a meeting point for different cultures?

Yes.

Where was the album recorded?

It was recorded in a studio in Paris and produced by Renaud LeTang, who's worked with Feist and Manu Chao.

It's a beautiful production, the cello and horn arrangements especially. Did you use a lot of longtime musical partners or did Letang bring in a lot of new people?

Before the recording, I and the guys I tour with stayed together for 12 days in a rehearsal spot and worked on the songs. Then we went into the studio with Renaud with what we had.

You have a very distinct guitar sound and style. Where does that come from?

When I arrived in Paris, I had the opportunity to go to a conservatory, but I decided not to. So I was self taught. That method has helped me do things in my own way. I don't even know the chords I play. "Is this an A, a C, or an O?" I don't care. I play what I feel.

So it's all by feel. Are there guitar players you look to as influences?

Absolutely. But it's not their technicality I find inspiring, it's the humanity, the feeling. And I admire musicians who have managed to be themselves. That's something hard to do in today's society: be YOU. How can we survive in this society as musicians, without worrying about what other people are doing? It's not easy, but when you can achieve it, it's amazing.

Yes, it's hard to resist commercial pressures, to conform to the ideas other people have about how your music should sound. Have you experienced that sort of pressure?

Yes, but it was more about the language: people were telling me I needed to sing in French or English, but I explained to them that the most famous contemporary French singer in Paris, he'll probably never go to perform in Sweden, say. And his counterpart in Sweden won't be performing too much in Paris. Meanwhile, I'm singing in my mother tongue of Bassa and I'm going to Sweden, Denmark, India, Japan, China.

You're singing in a language unknown outside Cameroon, so that allows you a greater freedom, in a way, to go wherever you want.

Yes. So why would you want to limit me to French?

Blick Bassy - Ngwa (Official)www.youtube.com

Why indeed. A couple of silly questions to end on: if you could name yourself after any object in our solar system, which would you choose? Which heavenly orb should be known as "Blick Bassy"?

The sun.

If you could jam with any dead musician who would it be?

Mmmm, Mavin Gaye.

Yes!! Anybody else?

Nat King Cole. And [blues legend] Skip James, of course.

Right! I keep hearing that second name associated with you.

My father listened to him all the time in Cameroon. And I was further introduced to his music when I became a musician. He sang with nothing but his own powerful emotions. I wasn't even sure it was in English; it felt really close to what I was hearing.

One more silly question: what is your desert island food?

It think it'd be something we call in my country "jazz." It's just beans cooked in the Cameroonian way, with plantain. It's amazing.

Are you going back to Cameroon soon or do you have a lot more touring to do?

- I would like to be, but I don't feel comfortable going there with the political situation as it is at the moment. I have a friend in jail, actually. His name is Valsero, a musician. He was protesting, speaking out against the government, and they put him in prison.

One last question: is there anyone you would really like to collaborate with on a future project?

Yes, sure. I really love [composer/bass player] Esperanza Spaulding. She's a good friend. I should give her a call. [laughs]

Related Articles Around the Web

Blick Bassy

Blick Bassy